The late 1970’s were a terrible time, if you were living in the scary, dark tenements of a large city in post-industrial decline, and saw no plausible way out of the urban decay. To see the Bronx burning from the aerial view of a helicopter during the World Series is one thing – then add the blackouts and the Son of Sam moments, and you can understand the desire to leave all of that behind for the suburbs, if only in service of raising a family and securing its future.

Despite it all, New York City and many other urban centres managed to resurrect and reinvent themselves in the ensuing decades. The exodus was long, but temporary, and the kind of talent that naturally came from the streets of the Five Boroughs in the early post-war era (Barbara Streisand, Woody Allen, and countless others), would soon come from places just beyond the city limits in the adjacent suburbs (Billy Joel, from Hicksville, Long Island) or maybe the furthest from New York City as a place could get and still be in New York City (Joan Baez, Staten Island).

Or they could come from Park Ridge, New Jersey, a comfortable Bergen County suburb less than an hour from Midtown Manhattan. What a difference crossing a bridge or tunnel, then driving some miles towards the First Mountain, makes for a famiy on the path of growth. Many Irish Americans picked places like Park Ridge. and never looked back. The Irish-American population of New Yotk City was over 20% after World War II, it is 6% today. 6% of 8.5 million is still 500,000 people, and at least as many as that now live in the adjacent suburbs.

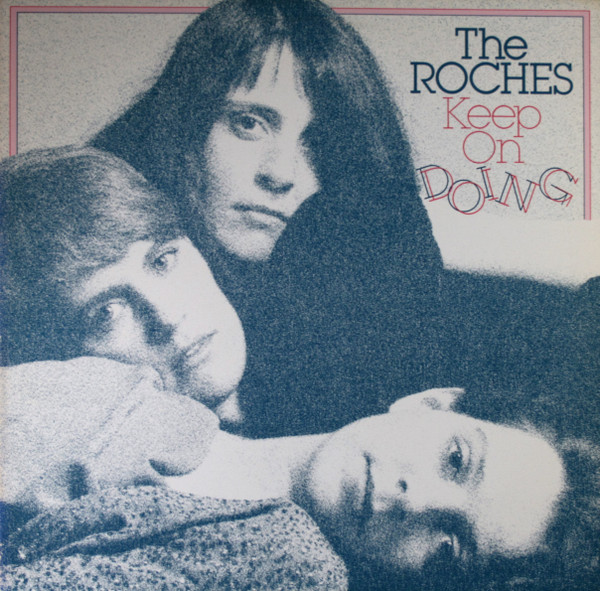

The adjacent suburbs, that’s where the Roches come from. Not a household name by any measure, but nevertheless an interesting group of sisters who sang, who were first-generation Irish Americans, and who could only have attained a small ampunt of notoriety and fame in the decades that bore witness to the suburbanization of the nation’s metropolitan areas. Pair this with the fact that the late 1970’s were a period where pop music’s influencers (record producers and existing musical talents) was comfortable with experimentation, taking chances on obscure aartists and less mainstream viewpoints and perspectives, and you can see why the Roches only could have come to pass at that point in modern history.

Taking the classic Hibernian recipe of families as harmonizing singers and adding some unique traits to their musical formula, they are nothing if not quirky. Occupying three distinct portions of the register., the baritone of Maggie Roche (or at least, contralto adjacent) formed the lower foundation of their vocal output, and Terre Roche (terry, short for Theresa) possessed a thin but spirited soprano. In the middle was Suzzy Roche (rhymes with fuzzy or Muzzy). There were no male Roches of this family’s generation to provide any vocal support – that, in and of itself, made them relatively unique in America..

It should ve noted, that in the UK and Ireland, there were the Nolans, but they are sisters who inudulged in squeaking the packing peanuts of baseline feel-good pop music, and the US had the Pointer Sisters, but they were an entirely different kind of sister group, and in the 1980’s they would become next-level.

The Roches were folksy when folk was on its way out, and they were a family band in an era where that type of structure was becoming somewhat unpopular, for four-tet rock bands and solo artists were becoming much more in favor. Two of the three Roche sisters got their first big break by being Paul Simon’s backup singers during his There Goes Rhymin’ Simon tour in 1973. Maggie and Terre Roche (Suzzy was not yet a Roche) used this early exposure to create a first album release in 1975, Seductive Reasoning.

What an album title for two teenage girls to pick! The songs on this album are not necessarily brilliant, but there is a uniqueness that is worth paying attention to. The song “Underneath The Moon” features a fabulous Moog synthesizer accompaniment – a vanguardian choice of instrumentation, especially for folk pop music. The only other Moog featured prominently in that era in this type of work would maybe be the songs on Gordon Lightfoot’s Sundown – see the song “High and Dry”. The song titles, in and of themselves, bespeak of a kind of unpretentious, feminist-by-doing and not feminist-by-saying, attitude that is refreshing. “If You Emptied Out All Of Your Pockets You Could Not Make The Change”, “Burden of Proof”, “Jill of All Trades”, these are epic, evocative song titles, even if the contents therein are less inspiring. Morrissey would be jealous of these kinds of song titles.

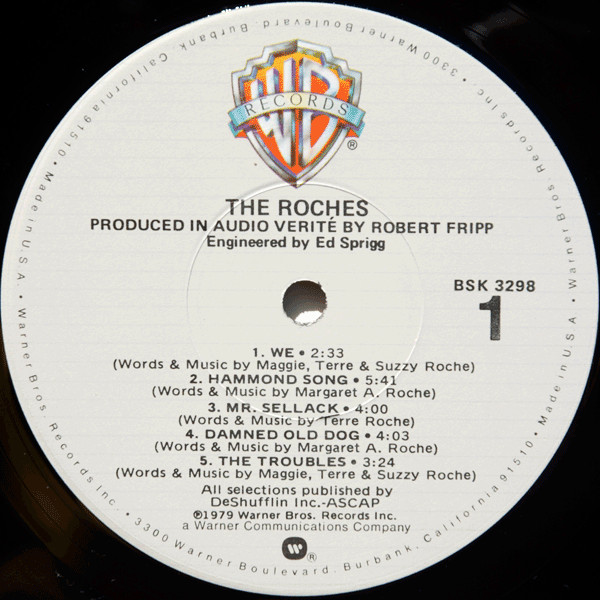

The Roches’ biggest moment in the relative spotlight was in the album release, The Roches, in 1979. This is the one and only album anyone remembers of theirs, and while mostly music nerds and music nerds alone remember this album, it gained exposure for one of two reasons – it was produced by Robert Fripp, the virtuoso King Crimson guitarist and talented music producer. His production techniques, he surely felt, was deserving of a name in and of itself, calling it “Audio Verité”.

Note the subtitle: “Prouced in Audio Verite by Robert Fripp”.

Note the subtitle: “Prouced in Audio Verite by Robert Fripp”.

The pretentiousness is charming, because his bona fides are very real, and this album has a warm yet crisp production value that is pretty much perfect and bespoke for the folksy harmonies of the Roches. It captures the intimacy of a live folk performance, and pairs it with the technical mastery and expperimentation that the best musicians and producers of the 1970’s could conjure up. Only a few momnents in Joni Mitchell’s catalog could manage to capture this seemingly disparate set of priorities – Jaco Pastorius and Joni itself possessed that mix of art and process in a few songs like “Amelia”, “A Strange Boy” on Hejira, or “The Jungle Line” or “Don’t Interrupt the Sorrow” on Hissing of Summer Lawns. Other than the male-dominated form of progressive rock, there are no analogues during this era of popular music.

The Roches’ songs will make you laugh, guaranteed. Their frequent use of quirky, funny observations are humorous in and of themselves, and their occasional lack of earnestness and their choice of topics has a teenaged, juvenile feel, but in the very best of ways. The cynicism of looking behind one’s shoulder at what the cool kids are doing is nowhere to be found in The Roches, or anywhere really in their body of work. As often as they attempt to inject corny jokes and witty ‘bon mots’ inserted inside serious topics (at least for barely post-pubescent teenaged girls), they also address serious topics with a frankness that is rare. What begins as a roll of the eye might very well end up in tears, as you travel the journey of songs through their LP release.

Perhaps because they were elevated to a wider audience by mentors who wanted to champion them and their differentness (Paul Simon, Philip Glass, and Fripp, among others), the Roches managed to create a set of songs that has the musicianship and mastery of adulthood, but retains the unbiased, open-minded perspectibve of adolescence, and they did so with relative freedom. The collabortion of celebrated, more mature folks like Robert Fripp, gave this album a lot of exposure, but it did not sell like hotcakes.

The sales statistics of The Roches were not that great – depending on how much Robert Fripp charged for his services. it might have barely broken even. And it was not the kind of record that would have very broad appeal, but would rather serve a a time capsule for a unique moment in time.

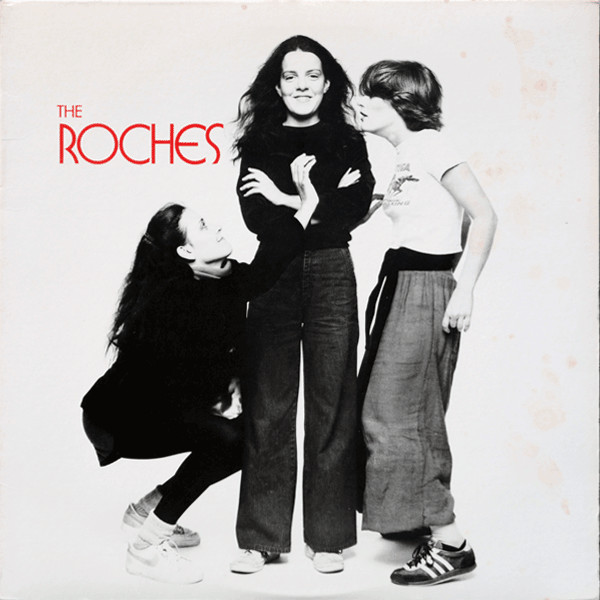

Like many music nerds (or Nurds). I saw the cover sleeve of The Roches at least a dozen times in used record shops and garage sales before I ever bothered to buy it or listen to it. Other than Linda Ronstady’s less-inspiring releases, or maybe a copy of “Stars on Long Play”, I can’t think iof an album that was so widely purchased but not actually listened to all that much. Any copy of the Roches I saw at my record stores of choice (Waterloo Records in Austin, or Cactus Records in Houston) were almost new in feel, sometimes the saran wrap still on the sleeve. I ignored it for a long time.

The use of ITC Busorama as the album’s typeface is great. Their “Born To Run” meets the Misfits poses are geometrically proportionate and to the point. The Adidas sneakers of Suzzy Roche are in fact just cool enough for school.

Just because the Roches’ style and vibe were lost on most music buyers in the late 1970’s and early 1980’s, doesn’t mean that it didn’t have its champions, now or then. I finally bought a used copy of The Roches a good decade after I had first seen that nerdier-than-thou, self-assured album cover, the three girls looking pretty much like antecedents of the cool artsy girls that occupied a rung of the aspiration ladder in my affluent, college-track high school. It reminded me of the band Fanny, or the Misfits, or other “cool girl” groups, as well as the lighter-hearted all-female iterations of riot grrl music like The Donnas or pehraps the new wave ladies of The Go Go’s, posing playfully with wet towels on their head.

I had never paid anything but the album cover much mind until I discovered that Robert Fripp had produced it in “audio vérité”. Coinciding with my emerging interest in prog rock, art rock, anything with technical mastery from the golden era of LP records, I decided to purchase The Roches and give it a solid listen.

I was not disappointed. In fact, despite the very uneven quality of each song (some songs are too cute to be taken seriously, some are too twangy and Plastic Paddy to be enjoyed), the moments where they get it right are astounding.

The Roches’ lack of boundaries in terms of what they chose to write songs about is such a treat, a time capsule of obscurity that nevertheless provides a macro view into teenaged girls’ viewpoints. Think “Are You There God, It’s Me, Margaret?”, or perhaps “Are You There God, It’s Me, Maggie Roche?”.

The standout tracks on The Roches are “Hammond Song”, “Runs In the Family”, and my personal favorite, “Quitting Time”. Each of these songs is so very different from the rest of folk-pop music in terms of their choice of subject and even their structure. They are peerless in their mix of earnestness, realness, and feature motifs you’ll never see in the lyrics of other songs of this time.

“Hammond Song” was written, and took place, during the interstitial moment between their first album and their second. The feedback they received from their record label on what could be improved upon from Seductive Reasoning was not musical in nature, bur instead, it was a complaint that they were not physically attractive and should at least “wear hipper clothes”: Negotiations started to become difficult and dicey, and the whole thing turned off Maggie Roche, the main lyricist, so much that she walked away from the creation of the album and made the impulsive decision to go live with her boyfriend, who had moved to Hammond, Louisiana, to open a kung fu studio (how very mid 1970s!).

Like the kid who packs his suitcase too full when he’s threatening to “run away from home”, or the college boy or girl who overstays their welcome on their European vacation in order to pursue a romantic fling with a local boy, the decision to relocate to a mid-sized town in Louisiana was a hallmark of teenage foolishness, very frivolous, and like all fantasies that are enacted in moments of contingency, something that might be abandoned with the same quickness and fervor as it was executed.

The song is basically an intervention of sorts, a familial reminder that making this decision was silly and not in her best interest, and that you can always come back to the comfort of your family, and can always correct your course. The other two sisters remind the eldest that:

“If you go with that fella, forget about us

As far as I’m concerned, that would be just be

Throwing yourself away, not even trying

Come on, you’re lying to me”

Paying attention to the lyrics, in and of themselves, and listening without prejudice, the slow, but processional pace of the song, is a great listen for those with the requisite patience. If you can endure the song’s langorous pace, you will be rewarded with the surprise of a song’s lifetime – a dazzling guitar solo from none of ther than Robert Fripp himself.

Known for his superior skills at the guitar, Robert Fripp is about the most awesome of guest musicians that anyone could dare dream of to grace their album. Brian Eno’s “St. Elmo’s Fire” from his album Another Green World features a guitar solo from Robert Fripp that has that rare, Frippian combination of technology and sheer skill. And the production values and the atmosphere present in David Bowie’s “Heroes” is completely attributable to Robert Fripp’s involvement in the creation of that song.

The guitar solo in “Hammond Song” arrives at about 2:08 in a song that is 5:46 in length, and it is a moment of “wow”. It is breath-taking, it is awesome, and it certainly is one of my favorite and unexpected moments in any pop song – it got me into guitar solos as a thing worth sometimes hearing again.

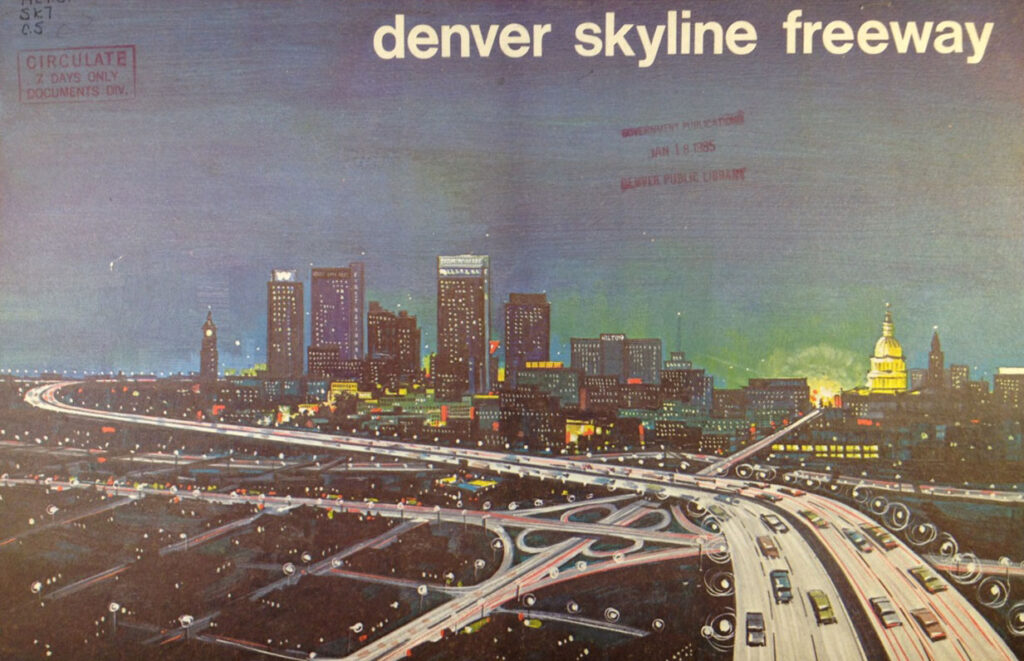

“Quitting Time” is another treatment of an unlikely subject – this time, sympathy for an industrial baron or CEO of a company that is filing for bankruptcy or otherwise ceasing to produce.

“Money is not the problem, ypu have enough of that”, the Roches begin. “Now you must close your office, put on your coat and hat”, they contunue.

The mise-en-scene is beautiful and melancholy – “now is the hour of quitting, twilight paints the town / old industrial skyline, how does the sun go down?”

One could easily imagine that a factory would be shut down and cease to operate in the industrrial nodes of New Jersey – Paterson or Newark, perhaps, but the attempt to engender a sense of sympathy and lamentation for a rich man who is probably as benevolent as a hedge fund manager who liquidates companies with rapier precision, is truly something different. It is so very ‘middle-class New Jersey’.

You feel a crepuscular, swan song tinge of sadness, as the sun sets on this nan’s factory and this man’s career, and the funereal feel that would come to desscribe the entire economic landscape of trhe Winters of Discontent that would come to typify the 1980’s and the decades after. This song describes post-industrial decline in such a personal way, in a way that has no eqhuivalent, except for maybe “Synthconicity II” the Police.

“Quitting Time” wraps up this nuanced and conmplicated type of moment in history with a sad, regretful harmonizing that is Irish lamentation in quintessence – the harmonies of the Roches’ three voices fit just as well in sending off an American boss as it would be lamenting the sad sighing of an traditional Irish folk song. “Quitting Time” is just as Irish as “It’s A Long Way To Tipperary” in my estimation.

The music that came after this album, and the devotion to the craft of music, would become quickly inconsistent and less remarkable for the Roches, in their subequent releases.

Nevertheless, their output on The Roches is a lovely milestone in modern American pop music, with its rare combination of Irish folk harmonies, New Jersey sensibility, and aural choreography of Fruppertronics, and if you appreciate rare talent and the works of those toiling in obscurity, there is no better example to listen to, enjoy and cherish.

– Matt Rutledge